Tongues of Flame

Tongues of Flame: custom pyrography & magic to discriminating musicians & magicians. Tattoo & Hoodoo for that Voudou that you do.Sunday, September 24, 2006

I love the way red oak blushes under the hot stylus, and I was particularly pleased with the effect of the design on the wood. The minute detail of the engraving, along with the "floating mountain" motif, gives the finished work the look of Japanese dry-point engraving.

As with the cedar bough used for "Death of A Man Who Loved Mountains (below), the "rough", unfinished edges and roughly planed surface seemed appropriate to a work comissioned in grief, which is, after all, simply ragged love.

Saturday, September 23, 2006

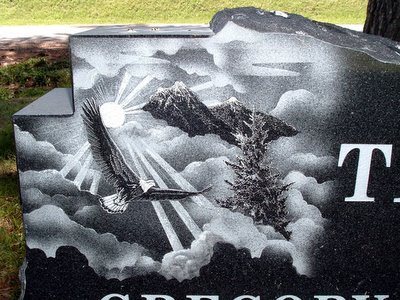

The following are pyrography memorials, in cedar and red oak. The narratives have been edited to removed all identifying information, out of deference to their families. Where specific information has been retained, it is because the spirits have spoken ambiguously enough that only those already familiar with the circumstances could decipher it.

I started this piece with the following information and requests. This was to be a memorial to a man who died young, the son of a woman of power in the West. Those commissioning it wanted it to include images of the Rocky Mountains, as well as wolf and elk tracks (his totems), and a reference to muzzle-loaded weapons, which he loved. The wood, a length of cedar, was donated for the memorial, a piece of kindling shaped by the blows of the axe.

| From Memorial Comm... |

Initially, it was my intention to plane and sand the surface smooth, as a better canvas for the images. When I held the wood, however, it spoke to me, and forbade it. The spirit of the cedar said “Death does not leave smooth surfaces. It strikes like the axe, splitting wantonly. It is time that wears smooth. Death is, for those remaining, violence and violation, and the shapes with which they make their peace with loss must be laid over the ragged fragments of what remains. You will do the same.” There would be no sanding.

Cedar is itself a holy wood, long consecrated to mourning, to purification, to comfort and guidance. The shape of the wood was also significant to me, smoothly ridged and furrowed like canyon walls, colored like a western sunset, smelling like ceremony under the hot stylus. The hole in the center could not have been more appropriate to the subject matter, for more than the merely obvious references to grief and absence. Among the western Nations, it has long been traditional to “kill” the vessels which accompany the souls of the dead on their journey by placing a hole in them. Supernatural beings, such as “Elk Who Does Not Die”, who are invoked here as companions and guides on the journey are represented as having holes or missing organs in various locations. Then there is the Sipapu, or hole of emergence, by which we ascend to whatever worlds come next in the evolutionary journey. But we will return to these themes in greater detail as I address the symbolism of the piece.

From the first moments of praying over, and working on, this piece, I have been powerfully impressed by two clarities: One is that this soul has begun its journey in a good way, without regret or suffering. This one knows his way home. The pain here (and I have trodden only the edges of it, a vast and suffocating grief, like struggling to breathe; but clean, for all its depth) is for those left behind. The second has been the presence of the Gan, the Great Powers of the Mountains, blindingly holy, fiercely pure, and lovingly indifferent to the flickering world around them. For reasons I do not begin to understand, these great Powers have taken an interest in this soul, and claim it as one of Their children. There are no more powerful guardians and guides in the long climb between worlds than These.

It was in the midst of Their overwhelming Presence that the vision came, of a silhouette, like a man formed of daylight. He stood just on the other side of an aperture framed by spruce boughs. Dazzling peaks burned in the air behind him. I record here what I was told:

(A bright light stood before me and declaimed;

On the death of a man who loved mountains)

“I would speak of mountains and of death

Death is a mountain

All our days lived in its shadow

All our footsteps taken in its foothills

But in the end, this is only living

It is death that is the mountain,

The ultimate and only real adventure

Small hearts do not seek mountains

Mile beyond mile of long and brilliant air

It takes courage to face the gulfs

Measuring oneself against forever

Mountains teach, they clarify; distill

They set you free

They do not care you love them

Or love you back

They lift

They do not carry

To love mountains is to love the struggle

Onward toward some dreaming summit

Against the pull of all we love below

And such is dying, if we are among

The lucky, and the blessed, and the brave

Those who love mountains

Oh, how we climb! We climb!”

The piece is burned on all six sides. As a medicine piece, it is appropriate that the Power should speak in all directions, so that a continual prayer would be offered, whatever its position, and so that the powers of all the worlds should be acknowledged and their assistance implored, both for the spirit having flown and for those who remain.

The mountains represented here are Mt. Blanca and the surrounding peaks, as seen from the San Isabel National Forest. They are framed on either side by the images of Gan dancers among the clouds. “Gan” is the Apache name of these Powers, the souls of the peaks, and their Guardians. They are also known as the “Defenders of the Faith”, the guardians of tradition. I have walked among these Beings, both in flesh and spirit, and tasted the smallest sliver of Their unspeakable grandeur. While They are beyond any power of man to compel or conjure, They sometimes, for reasons known only to Themselves, take an interest in individual human beings, who are then marked (not only in this life) as the Children of the Peaks. --- is one of these, moving through the world of dim shapes and half-remembered purpose with a kiss blazing on his brow like the morning star. He will reach the peak to which he ascends.

The mountains have their messengers, as well. For the indigenous nations, the guide among mountains is wolf. His is the voice by which the pain and sorrow of Earth rise to the ear of Heaven. It is a peculiarity of Wolf medicine, that this extraordinary guide forgets himself, and his purpose, until the need of another recalls it to him. Those who have wolf as their totem are often the same, full of wisdom and power they are not conscious of, until someone around them is in need. Then they amaze themselves by the clarity and insight that comes pouring out. Such unconscious holiness is powerful, and those who possess it (or are possessed by it) usually accomplish more than they could ever have imagined in their time on this world, leaving behind them a trail of quiet miracles and gently mended lives.

To the right of wolf lies a spilled powder horn. It is traditional among many nations to break the instruments of the hunter upon his death, and the image of spilled ammunition is an appropriate metaphor for the loss of youth’s potential fires

Beyond the streams of darkness which flow beside the fallen powder horn are seen a series of images, drawn largely from the Colorado rock art of the so-called “Fremont Period” The texture of the wood here is that of an arroyo. It seemed an appropriate place to invoke those ancestors to whom the land --- loved was sacred before all others, the ancients who first walked in these mountains and canyons, and who learned the names, the natures and the voices of the spirits of the land. The horned figures in particular are prehistoric depictions of the Mountain Gods, which find curious echoes in places like the rock art of North Africa. Thus the narrative of the piece is framed within the Gan, as is the story of this soul.

One of the greatest losses of this civilization, as it has repudiated the Powers of the natural world, has been the loss of understanding of the roles of those powers in the growth and evolution of the human soul. The Spirits of places and of geographic features, as well as of the four-leggeds and other natural phenomena, are teachers, guides, and essential characters in the drama of the spiritual journey. Who and what we are is shaped by them to a greater degree than most of us are now aware of. The land dreams us, and the dreams we carry help to shape what we become, in this world and those beyond. It is only the arrogance of man which blinds him to the fact that, while he shapes the earth, he is shaped by it. That while he moves among those who walk in it, they move within him. We have a place within the pattern, which shapes the pattern of our individual lives, which extend far beyond anything that is visible to us from here.

Central to the piece as both sculpture and poetry is the hole. This is death, the sacred absence, the portal where, according to Navajo and Apache tradition, “the black and white rise up together.” It is only through the presence of death, that coherence and pattern are achieved. Death gives meaning to everything we do, and do not do. Given an eternity in which to act, sooner or later all choices must be acted upon. The actions of an immortal are thus meaningless, the inevitable playing out of infinite possibilities. Only limits make choices meaningful. Only death gives our days their flavor in our mouths.

The awareness of death is the foundation of wisdom. Death is an advisor who never lies, who accurately and honestly tells us the worth of any decision. It is the knowledge that I will die. On the day of my death, how will I feel about this? The answer to this question is always an honest one. This is what we mean by the expression, “It is a good day for dying.” Not that we seek death, or as some meaningless boast about courage. It means, if I die today, I am living the life I meant to live. I am who I meant to be. My life will have been complete. The best preparation for a good and meaningful death is a good and meaningful life.

The piece is framed, along both lengths, by tracks of wolf, and of elk. The role of wolf as guide into the high places has already been addressed elsewhere in this narrative. Here it is enough to note that the tracks are those of a walking wolf, confidently pacing along well-known routes. The role of elk as guide and teacher will be addressed at the end of the work.

On one end of the timber is figured the red-headed woodpecker. This image is taken from Cherokee mythology, a version of one of the oldest stories men know. Anthropologists call it the “Orpheus” myth, after the Greek version, but it is found among human beings all over the world. In the Cherokee tale, which forms part of a much longer epic, the Daughter of the Sun is the first being to die. The priests and priestesses of the Cherokee nation send a delegation to the spirit world to bring Her back. One young man of the group, in love with the young Woman, impatiently opens the chest which holds her spirit on their journey back to the land of the living. The spirit is released into the world as the red-headed woodpecker, and the division of the living and the dead is made permanent.

This myth speaks to some of the most basic truths about death and grieving in the human condition. It affirms the power of love to bridge the worlds, and teaches that such bridges are by nature temporary, and cannot remain. It teaches that death is a process which itself changes the nature of our relationships to those we have lost. It is a teaching about the necessity of change, of the influence of time on love, however steadfast. Love remains. But it is not the same. It cannot be, while we remain among the living. To believe otherwise dishonors life and death alike.

On the opposite end is burned Coyote. What wolf is to the high places, coyote is to the barren places, the wildernesses in which the spirit wanders while in grief. There are ancient stories about how, when Wolf first died, his little brother Coyote stole away with Wolf’s heart in his mouth. Coyote is cunning madness, the craziness with which we are touched when someone we love is taken. To survive the journey through the valley of the shadow, it is a good idea to let Coyote carry one’s heart. That is, to indulge the madness of grief, to trust the process of mourning, even when it leads into apparent insanity. Only by trusting the “little madness”, by giving ourselves to our sorrow, are we capable of healing from it. Coyote is a scavenger, a devourer of the past. Pain that is not offered up, acknowledge and acted out, will rot and fester over time, and eventually poison the wells and springs of the spirit. Follow Coyote into the shimmering haze and dry exhaustion of your grief. This consummate survivor has much to teach those who mourn.

Finally we come to the figure of elk. Those who have studied Native traditions will be familiar with Elk as the type of charisma, of charm and sexual magnetism. Elk medicine is the power to bewitch the beloved, to draw the eye and heart of the object of desire. Elk sings to draw his mate, and his song has great power. It is elk who taught men to make music with which to enchant women, according to the stories. There is indeed some anthropological evidence that music may be the source of the human capacity for speech, and the urge to make it part of our ancestral mating behaviors. Those with strong elk medicine tend to be “lucky in love”, as well as the hunt, and may be musically gifted. This is elk medicine as it relates to the concerns of every day life, as it manifests in the world of human relationships. This is elk-among-men, the first elk.

Those who hunt Elk long enough to learn His ways, however, find clues to another role. In the words of Joseph Epes Brown, the biographer of the great prophet Black Elk, “Recorded information on the Oglala’s observations and accompanying views of the elk indicate special appreciation of the bull animal in particular. Among those qualities specifically singled out are his strength, speed, and courage. The powerful form of his massive antlers, and the skill with which he is able to travel with such horns through even the thickest cover, were discerned and appreciated.” To the hunter, elk was among the worthiest opponents and most formidable of the Natural Powers, a valuable totem and powerful guide. This is elk-as-he-is, the second elk.

But there is another component to Elk’s power, which requires some deeper effort to penetrate. This is Elk Who Does Not Die. This figure appears in the mythology of numerous Native American cultural traditions, and was often represented symbolically with elk teeth, which will remain when all other body parts, including bones, have decomposed and turned to dust. They outlast the lives of men, and have become symbols of eternity. Elk Who Does Not Die is always represented with a hole or mirror in his body, as a token of his essential transcendence of the temporal world. Only what can die is complete in this world. Elk Who Does Not Die is the Power responsible for enforcing the terms of the contract that all hunters, and ultimately all human beings, must come to terms with, that death comes when it is time. He punishes hunters who disregard death’s balance, or who act to cut short the rightful spans of their prey. He is the Guardian of the Balance, and the Wisdom which knows that there are limits even to death’s power. Elk Who Does Not Die is the third elk.

Finally, there is a convention in Cheyenne mythology, in which animals questing for the mountains give away their eyes to reach their goal, relying on the vision of greater powers and guides to carry them safely onward, and upward. The hollow eye of the Elk is a symbol of the give-away, by which the soul entrusts itself to larger currents, and is lifted up by them. It is the mark of one who has ascended. So let it be here. So it is.

Thursday, July 20, 2006

Prices vary according to size and complexity of the design, but are comparable to those of a reasonably priced tattoo of similar size and skill demand. If you have a budget, we can probably work around it. Contact me for details.

How It Works

You send me the instrument. It needs to be stripped of any paint or clear-coat, as these prevent the wood from taking the images which are burned into it. We talk by e-mail or phone. I ask strange questions. You tell me your ideas, what it feels like when the music is coming through you, what you want to capture or communicate in your music. Let me hear your work, or, if you don't have anything recorded, at least let me hear the music that moves you, that influences your sound. We'll talk about what you believe in, what you care about, what you dream of. Tell me about your favorite movies, books, ideas, painting, or comic-book characters. It's different for everybody, of course. That's the point, after all.

Then I do my thing: ceremony, divination, journeying. I listen for what your music is saying to me. I listen for what my allies have to tell me, or show me. I ask the instrument what it wants to be. I put the design together based on what I know, what I've learned from you, and what I'm shown along the way. I tell you what I get. You tell me if it works for you. I heat up the steel tips, call the spirits, and do the deed. You get a pimped ride for your internal landscape, along with a cd detailing the symbolism, influences, and meaning of the design.

The closest anology (in some ways) to what I do is probably tattooing. Prices for a design are comparable to those for tatoo work in a good shop (Actually, they're cheaper at the moment--take advantage of me while I'm still cheap and relatively unknown). Like a tattoo, the cost depends on the size, positioning and complexity of the design, and can range from one hundred to a few thousand dollars. Some people approach this process the way they would approach getting a tattoo, starting with a quarter panel (6"-8") and adding to it as time and experience dictate. If you have a budget, let me know and I'll work with you.

Time involved is also, of course, dependent on the size and complextity of the design. Expect at least 6-8 weeks for the completed piece (unless we're talking about something really small, or simple). Bigger pieces take longer, of course, but we'll agree on a mututally satisfying deadline before beginning. Each guitar is signed, titled, and numbered by the artist. See the portfolio of finished pieces for more detailed examples of how it all comes together.

TONGUES OF FLAME #4-STRING THEORY

“String Theory” is the 4th installment in the “Tongues of Flame” series. This number has related connotations in the cosmologies and intellectual traditions of a variety of cultures across the globe. In indigenous American cultures, this is the number of the cardinal directions, the primary reference points of the consensus reality. In the European Hermetic tradition, four is associated with the fundamental aspects of the material world, the four classical elements: earth, air, fire and water. In the Tarot, four is the number of The Emperor, of the material world as the product and object of consciousness; analyzed, penetrated, manipulated by and reflected in Mind. In Hebrew tradition, four is the number of the Manifested Divine Will. In science, four is the number of the known dimensions: height, width, depth, and time, and the four known forces of nature. It seems appropriate, then, that this guitar’s imagery should be concerned with the material world, with science, with mind, and with time.

This particular instrument’s biography is also significant in the choice of imagery. This guitar was a first (electric) guitar, a gift to the musician from his grandmother. This individual, in addition to being a considerable musical talent, is a scholar and an alchemist who has gone on to develop dazzling ability as a producer and sound engineer. It seems appropriate, therefore, that the guitar’s symbolism deals with origins and development, application and theory, and the nature of sound.

Finally, this guitar is the first of the series to go out into the world to a new owner. It therefore follows that its subject matter should be general in nature, propounding universal themes and catholic imagery, as opposed to the personal mythologies that form the narrative focus of all other “Tongues of Flame” works to date.

The title of the guitar, “String Theory” is a reference to the current world-view of science, and to the idea of the guitar as a model and manifestation of the most basic forces that shape reality. In the beginning was not the Word, but the Note, and the voice of the guitar (and by extension, all stringed instruments), is in some sense an echo of Omkara, the Music That Sustains the Spheres.

The concept of string theory, radically simplified, is the idea that the fundamental structures of reality are a variety of “string”, the vibrations of which produce the patterns that we perceive as sub-atomic particles and energy. In the words of Daniel Green, a professor of physics and of mathematics at Columbia University and a leading string theorist;

“The fundamental particles of the universe that physicists have identified—electrons, neutrinos, quarks, and so on—are the "letters" of all matter. Just like their linguistic counterparts, they appear to have no further internal substructure. String theory proclaims otherwise. According to string theory, if we could examine these particles with even greater precision—a precision many orders of magnitude beyond our present technological capacity—we would find that each is not pointlike but instead consists of a tiny, one-dimensional loop. Like an infinitely thin rubber band, each particle contains a vibrating, oscillating, dancing filament that physicists have named a string.

Although it is by no means obvious, this simple replacement of point-particle material constituents with strings resolves the incompatibility between quantum mechanics and general relativity (which, as currently formulated, cannot both be right). String theory thereby unravels the central Gordian knot of contemporary theoretical physics. This is a tremendous achievement, but it is only part of the reason string theory has generated such excitement

String theory proclaims, for instance, that the observed particle properties—that is, the different masses and other properties of both the fundamental particles and the force particles associated with the four forces of nature (the strong and weak nuclear forces, electromagnetism, and gravity)—are a reflection of the various ways in which a string can vibrate. Just as the strings on a violin or on a piano have resonant frequencies at which they prefer to vibrate—patterns that our ears sense as various musical notes and their higher harmonics—the same holds true for the loops of string theory. But rather than producing musical notes, each of the preferred mass and force charges are determined by the string's oscillatory pattern. The electron is a string vibrating one way; the up-quark is a string vibrating another way, and so on.

Far from being a collection of chaotic experimental facts, particle properties in string theory are the manifestation of one and the same physical feature: the resonant patterns of vibration—the music, so to speak—of fundamental loops of string. The same idea applies to the forces of nature as well. Force particles are also associated with particular patterns of string vibration and hence everything, all matter and all forces, is unified under the same rubric of microscopic string oscillations—the "notes" that strings can play.”

The images on the back of the guitar all relate, in one way or another, to this theme of archetypal musical string, as it is exemplified in mythology, in metaphysics, in science, in history, and in the development and dissemination of stringed instruments, in particular. Like any good current model of reality, its effects are entirely relative. The story or associations evoked depend on the direction(s) in which the images are traversed by the eye.

Perhaps the simplest level to start with is the historical, which traces milestones in the development of the guitar through time. The stump filled with vibrating water at the base of the guitar serves (in this regard), as a reference to mythical or prehistoric time as a kind of chronological threshold for the story being told, an “In the beginning” from South American indigenous mythology. Dancing in ecstasy just above the surface hangs the “small sorcerer with a musical bow”, one of several composite creatures found in Les Trois-Frères Cave in the Ariège in southern France. The figure has both human and animal characteristics, and at 17,000 years old, is considered by many scholars to be the oldest representation of a stringed instrument in human history. He dances as a shaman among the Sons of Tate (to Whom we will return later), exemplifying the early use of stringed instruments as a means of contact and communication with the world of the Spirits, and an interface between the chronological narrative and the spiritual that we will explore later.

The figures of Anubis & Thoth play an Egyptian bow harp, and a Mesopotamian lyre, respectively. Both instruments date to ca. 2,500 b.c. That Thoth, who is the Greek's Hermes, is handing a turtle shell lyre to Apollo is a reference to Greek myth, wherein Hermes makes the 1st lyre out of a turtle shell as a gift to Apollo, the God of music. Significantly, the kissar is an ancient north African stringed instrument actually made of tortoise-shell, and may represent the ancestor of all modern guitars.

The second symbolic theme, the development of models of reality, is constructed from the center of the back of the guitar outward, represented by three concentric rings of tile work.

The first circle of tile work consists of the plates of the turtle’s shell. This image represents the mythical or archetypal view of reality, embraced by most indigenous cultures as well as by the root civilizations of Western European tradition, in which the structures and patterns of the material world were seen as expressing an underlying spiritual and ethical aesthetic, something essentially deeper and larger than the merely human, in which man participates, and can appreciate, but is ultimately not the master or the maker of.

`The second circle consists of a tile work pattern devised by 16th century German mathematician Johannes Kepler. The tile work is periodic, meaning that it is possible to predict from any portion of the pattern what the remainder will look like, and that the pattern repeats itself across space at regular intervals. The imagery of this pattern, with uniform stars nestled in an endlessly repeating network of rational shapes, is a lovely metaphor for the emergence of the rational, or scientific, world view. It is this perception of a clockwork universe, the product of linear, predictable processes, which forms the heart of the scientific model of reality, as it emerged from the minds of Kepler and his peers; men like Newton, Galileo, Brahe and Copernicus. Their universe was rational, comprehensible if not completely comprehended, with uniform laws that resulted in endlessly repeated patterns across the scale of objects and phenomena. It was this model of reality which gave rise to the technological civilization of Europe, which would dominate human thought for half a millennium

`The outermost circle is formed of Penrose tiles. These tiles are named after their inventor or discoverer, Sir Roger Penrose, a leading quantum theorist and mathematician. Penrose tiles are aperiodic, meaning that the pattern is repeated randomly, if at all, across infinite space, and that it is not possible to predict, on the basis of any portion of the pattern, what the remainder will look like. This image is a perfect metaphor for the emergence of the post-rational view of reality predicated by modern physics, a model of reality embracing the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle, Einsteinian Relativity, and Chaos Theory. In this model of reality, the greatest precision science can achieve in its description of the world around us is a prediction of probabilities, a fuzzy universe forever being defined by the act of observation, a universe in which reality has proven not only to be stranger than we have imagined, but possibly even stranger than we can imagine.

A third layer of symbolic imagery occupies the central column of the guitar back. This symbolism revolves around the cord or string which links the body to the soul, and the soul to its source and its destination. The roots of this imagery run deep in the mythology of cultures the world over, on every inhabited continent. It is expressed here in the images of the Sons of Tate, the Four Sacred Directions, from Lakota mythology, William Blake’s Urizen, the God of Boundaries and Limits, the Fates from Greek mythology, and Maui, from Polynesian myth.

The Four Directions are depicted as sun-dancers, the cords which tether them to the ceremonial tree are transformed into the strings of the kissar, in this instance an emblem of the living earth. The tension of these cords, experienced by the conscious mind as pain or resistance, determines the tonal range of the instrument, just as the experience of pain tethers us to the world, and determines the possibilities of our expression in it. The dancers represent the possibilities of will and self-determination, the movement of the Spiritual Cord from its lower, or immanent tether point. The Dancers are also a reference to a Lakota prophecy, endorsed by Grandfather Archie Fire Lame Deer, that there will come a prophet, also known as Tate, who will teach mankind how to heal with sound.

Above them kneels Urizen, a figure Blake saw as a fundamental principle of reality, the Law of Limitation. He is posed as in Blake’s original print “Urizen Measuring the Void”, only now the points of his calipers serve to determine the degree of tension on the sun-dancer’s cords. He is Divine Necessity, the movement of the Spiritual Cord from its upper or transcendent end. He kneels in the midst of a sphere of eyes, representing the transcendent seat of Consciousness, the place “Where What Is Willed Is Done”. (The single eye in the turtle shell represents the possibility of Immanence in the material world, while the eyeless surface of the water pooled below represents the initial phase of manifestation, as yet unaware and untempered by incarnation. The juxtaposition of the cieba-stump water and the troubled sea in which Maui fishes above locate the subject of the mural as that of the consensus reality and its components, between the waters below and the waters above).

Emerging from the Primum Mobile behind Urizen stand the Three Fates: Clotho, Atropos, and Lachesis, the Spinner, the Measurer, and the Cutter of the thread of life. Their position behind the abstract Principle of Limitations implies a doctrine of individual fate as potentially transcendent of the universal forces which compel this reality, notwithstanding the very real limitations imposed on the individual lifetime by its context in the material world.

The final figure on the guitar back is that of Maui, depicted at the seminal moment in Polynesian myth when, with a fishing line woven of his own hair, and the hei-ma-tau, a magical fish-hook fashioned from his grandmother’s jawbone, he fishes the island named after him up from the depths of the primordial ocean. In this context he represents the motive and mechanism of evolution, “The Great Work” of universal redemption, toward which all creation continually strives.

Finally, the front of the guitar contains an image of the artist in the act of producing Pneuma, fanning the spark of the Ohm into the substance of the stars. This image is itself a prayer, a blessing, a magical act; a recapitulation of the act of offering up this artwork into the material world in the intention of creating a lasting and enlightening contribution to the Great Work.

more pics available at: http://picasaweb.google.com/tonguesofflame

Wednesday, July 19, 2006

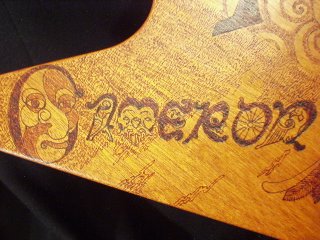

The Triquetra is the third guitar in the Tongues of Flame line. Designed as a birthday gift for the guitarist (Garret Thorne of Minus The Star), it came with a few specific parameters. Those commissioning it (his wife and friends) wanted the Chinese characters that are painted on the musician’s guitar case (peace, beauty, health, and prosperity) reproduced on the back of the guitar. They wanted the names of his two sons on the back as well, and “something Celtic” on the front, as a quarter panel.

I set the Chinese characters in a column, descending the back of the guitar.

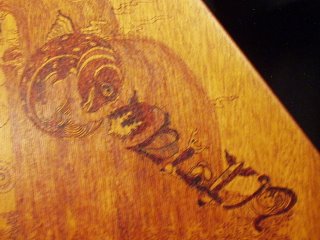

They are cradled in the smoke rising from the “Pearl of Happiness”, the traditional object of desire for dragons (Cameron) and phoenixes (Collin) in Chinese art, just as the qualities that the characters represent arise from self-knowledge. The boys’ names emerge from this column as branches from the central trunk that represents their father.

As a stylistic bridge between the Chinese calligraphy on the back and the “something Celtic” on the front, I have spelled out the boys’ names in anthropo- and zoomorphic letters in the tradition of the Book of Kells, one of the most celebrated examples of illuminated writing from the medieval Celtic tradition of literary art, completed in 800 A.D. by the monks of St. Colm Cille on Iona.

The symbolism of the letters, individually and collectively, relates to the boys’ natures and their destinies.

Cameron is the first born, and first named. The name “Cameron” is of Gaelic derivation, and means “Bent Nose”. There is an entity by this name among the stories of the Hadenausee, the Long House People. They call this powerful spirit “Elder Brother”, and explain that he existed prior to the creation of the world, so that when The Mystery made the cosmos, Elder Brother was shoved aside—hence his eternally crooked nose.

This Power is a great healer, and teacher; One who has the power to speak against death, and to drive away sickness, and His visage is framed in the capital “C” of “Cameron”.

The Allies say that this child is the latest incarnation of an ancestor soul, one that has almost completed its journey around the wheel of existence. They say that this soul has put on flesh to wrap up unfinished business, to attend to matters arising prior to this incarnation. Thus, like Bent Nose, this one existed “before the creation”. Like Bent Nose, this one will be a healer and a teacher. Like Bent Nose, this one may find himself a little cramped by the confines of a physical existence. There is more soul here than there is room for in the flesh. This will be both his strength and his challenge in the world.

The “a” of his name is partially formed by the juxtaposition of an arm and hand holding a bishop’s crosier, and a cloven hoof. This contrast represents what will be one of the central lessons of Cameron’s life, reconciling the nobility of his nature with the drives and impulses of his flesh. This child will hold himself and others to very high standards, and may be bitterly disappointed when those standards are not met. He has too generous a heart to judge others too harshly, once he has matured, but he may prove a fierce critic of what he sees as his own shortcomings.

The cranial arches of a Janus-face, a traditional theme in Celtic artwork, form the “m”. Here again the Allies speak of the child’s spiritual and physical natures, but this time in terms of their potential for integration. At those moments in his life when Cameron has managed to reconcile his ambitions with his condition, he will be capable of achieving something greater than either. There is a potential here for the development of remarkable skills, if not genius.

The central shaft of the “e” consists of a hand outlined in flame. There is a dual reference here, both to the “Shining Hand” of Celtic mythology and to the “burning hands” of a healer. The Allies are clear that this child will work as a healer among men, whether as a physician of souls, minds, or bodies (or any combination thereof). They say that there is a purifying flame in this one, a fire that will burn away suffering, and give light to those who wander in shadow.

The “r” is formed by the curves of a skull and jawbone. In both Celtic and African mythology, the head is viewed as the seat of the soul, a symbol of the identity’s survival of death. Cameron will not often be strongly influenced by other people. He has a solid sense of his own identity, and will always be an “older” child than those around him. He is internally directed, and his instincts will prove sound. They will direct him toward his purpose in life, and he will never lose his way for long, as long as he is capable of listening to his own deepest voice.

The “o” consists of a solar wheel, an emblem of the Light that does not fade. Cameron will always retain within himself a sense of what he has come here to accomplish, a place within himself where the Light in which he was created continues to shine. Heaven has an investment here, one that It will labor to bring to fruition. Cameron has only ever to look up, to rediscover his origins and his direction.

A peacock roosts in the arch of the final “n”. In Celtic art, the peacock is an emblem of both the starry night sky and the resurrection. Both reflect the persistence of light through time. It is this that Cameron embodies and that he has come here to learn about himself. The world will be a warmer, kinder place while he is in it.

The letters are set against a background of clouds and vapors above an unfurled wing. The Allies say that this child is a son of Oxala, the Power of the Heavens. They say he will always be reaching for stars. There will be moments when the clouds obscure the lights of heaven. The sky is not lost, even when it is not seen. Clouds pass, but stars remain. And do not be too surprised to one day find that he has collected handfuls of them.

Collin is the younger of the two boys, and their birth order is a reflection of their natures. His name, derived from the Greek, can be translated as “conquering child”. In Gaelic, it means “of the hazel”. Both themes are interwoven in the symbolism of the letters of his name.

The background against which the name is framed is the Pool of Wisdom of Druidic tradition, in which the oldest of all living things, the Salmon of Knowledge, feeds perpetually on the fruits which fall into the well from the sacred hazel tree, the source of all understanding. Five streams emerge from the pool, which are the five senses of the human body. This eldest of all creatures, dwelling in the continually upwelling (hence constantly “newborn”) waters, forms the capital “C” of “Collin”. This theme, of wisdom in innocence, is one that will prove paramount in Collin’s life.

The “o” and first “l” continue the Celtic motif, depicting the fruit, bough and leaf of the hazel tree. Characteristics associated with the hazel tree in human nature are mental and verbal acuity, communication and eloquence, perception, knowledge, and (sometimes sarcastic) humor. Collin will not be easily deceived or misled (by anyone other than himself). He will be charming and socially gifted, charismatic and smooth- (if sometimes sharp-) tongued. He will delight in interactions of all kinds, and in the acquisition of knowledge. His is a playful, sometimes mischievous nature, his inheritance as the spiritual offspring of Eshu Elegba, the Youngest Child of Heaven, and Master of the Crossroads.

The second “l” is formed by the arm of a shadowed warrior who holds a blazing torch in one hand, while a sword held aloft in the other is the letter “i”. This is a reference to the “conquering child” of Greek etymology, whose victory brings light into darkness and casts out fear. On the blade of the extended sword is engraved the ogham letter “coll”, (hazel), from which “Collin” is derived. Ogham is an alphabet or syllabary of sorts used to write very old Irish, from the 3rd to the 6th century in Ireland, Scotland, and Wales.

Finally, the swaddled infant resting in the crook of the “n” is Taliesin, the Star-Brow, a great wizard of Celtic mythology. In the myth, he steals the knowledge of magic that the Goddess/sorceress Ceridwen had intended for her own hideous son, “Affagdu” (Utter Darkness). The Goddess pursues him, and the two take on a number of forms in the course of the chase, until the young wizard shape-shifts into a grain of wheat. Ceridwen becomes a red hen, which swallows the grain. Nine months later, Ceridwen (Who is also the Great Mother of Celtic tradition) gives birth to a beautiful boy, whose brow shines like starlight. Even though she recognizes her former enemy, she finds that she loves the child and cannot bring herself to harm him.

Finally, the swaddled infant resting in the crook of the “n” is Taliesin, the Star-Brow, a great wizard of Celtic mythology. In the myth, he steals the knowledge of magic that the Goddess/sorceress Ceridwen had intended for her own hideous son, “Affagdu” (Utter Darkness). The Goddess pursues him, and the two take on a number of forms in the course of the chase, until the young wizard shape-shifts into a grain of wheat. Ceridwen becomes a red hen, which swallows the grain. Nine months later, Ceridwen (Who is also the Great Mother of Celtic tradition) gives birth to a beautiful boy, whose brow shines like starlight. Even though she recognizes her former enemy, she finds that she loves the child and cannot bring herself to harm him.

In this myth, the Allies refer to Collin’s nature as an infant trickster, his charm and the grace that shines through him, as well as to a soul who has found its way to the womb of this woman of power, herself a daughter of Ceridwen. There is considerable magic in this child, which is both his strength and his challenge in the world. It will take time for him to grow into his gifts.

In this myth, the Allies refer to Collin’s nature as an infant trickster, his charm and the grace that shines through him, as well as to a soul who has found its way to the womb of this woman of power, herself a daughter of Ceridwen. There is considerable magic in this child, which is both his strength and his challenge in the world. It will take time for him to grow into his gifts. For all Collin’s intelligence, there will always be something of the “little brother” about him, a perpetual childlike playfulness that is his essential nature, and which cannot be confined too closely without damage to his spirit. The Lakota call this energy “Okanga Ska”, the eye of innocence, which sees clearly. For all his perceptiveness, however, he will always be something of a mystery to himself, and his sparkling wit and intellectual ability can also serve to distance himself from emotional risk, and to conceal a profoundly sensitive emotional nature. His delicate antennae provide him with the ability to love with rare skill, as well as the temptation to use his rare sensitivity as a means of avoiding intimacy. He will have finely tuned nerves, and may suffer from nervous tension and headaches. He will require help to develop the discipline necessary.to maintain his exquisitely sensitive mind and body in balance. Otherwise, he could develop a tendency toward indulgence and excess that will be difficult to overcome later in life. His challenge in life will be to preserve his innocence and joy in the face of all the knowledge he will so voraciously acquire about the world. The world will be a brighter, more joyful place while he is in it.

The motif of the front panel is known as “The Beard Pullers”, and is taken from Pre-Christian Celtic stone monuments. In this instance, it represents the bond of shared destinies and karma that unite the musician with his sons, bonds that cannot be broken by life, or by one’s own actions. Through their struggles with their own attachments and with one another, a circular, rhythmic perfection is born. Likewise, this family will find its spiritual depths in the relationships of its members. They are teachers to one another, and the bonds between them will suffer no lasting disruption, and will prove a continual source of guidance and balance.

Nothing male exists in and of itself. The Beard-Pullers are surrounded by three Triquetras, the central image of the guitar. Like the Beard-Pullers, the Triquetra is an example of Celtic triple-knot work, a common theme in Gaelic art and mythology. Initially, the Triquetra represented the Triune Goddess of the ancient Celts in her forms of Maiden, Mother and Crone. After the adoption of Christianity, it came to be seen as a symbol for the Trinity. Here it is used in its older, matriarchal context. It is an emblem of the source and ultimate goal of the Beard-Pullers, a triune balance of perfect, organic equanimity. It is She who is Mother, Wife, and Guide, the Wheel on which these three fates are balanced. It is to Her, in Her aspect as Fata Morgana, Our Lady of Destiny; and to all the Powers referenced in the work, that the voice of the guitar rises in continual prayer. The Allies have said that it will not pray in vain.

Amen.

more pics available at: http://picasaweb.google.com/tonguesofflame